Alma Mater: On body donation, cell migration and morphogenesis

Bianca Millroy

We gather around the hospital bed in late December 2022 where my Aunty Gail lies, brittle but accepting of the terms on which the cells of her body will soon embark on their mass migration from life to death. Gail is my mother’s sister and the eldest of five. For decades now, her body has been under siege. Cancer has claimed sovereignty over her cells, first in the form of breast tumours, then spreading, node to node. Now, her diagnosis is terminal, her days and breaths numbered. Her body is withering, curling up, transforming.

Aunty Sue, the second eldest, stands beside me in the hospital ward. ‘I barely recognise her,’ she says. I have seen photographs of my mum and her four siblings at various stages of their lives – all of them dark-haired and olive skinned. The decades have added lines and streaks of grey, but little else has changed. Watching Sue grasp her sister’s hand—the papery, sallow complexion—my eyes are drawn to the stark differences between them.

There are two types of cell death: apoptosis (programmed cell death) and necrosis (caused by lack of blood flow). Apoptosis – Greek, meaning “falling off” as leaves from a tree. The acceleration of cell death at the end of life is a thawing river: slow, and then fast. For my aunt, it is autumn and soon, winter will cover her, a soft blanket.

~

There are four stages of cancer metastasis:

Step 1: invasion and migration.

Step 2: angiogenesis (formation of new blood cells) and intravasation (a cell entering the circulation and passing through the wall of a blood vessel into the vessel itself).

Step 3: survival in the circulation and attachment to the endothelium.

Step 4: extravasation (exiting the circulation) and colonisation of tissues.

~

When my 90-year-old Nonna flies in from Far North Queensland to be with Aunty Gail near the end, it occurs to me that there is something inherently cruel about outliving your own child. But the matriarchs of my mother’s family are strong-willed and steadfast. Their hands are kept busy making cups of tea and fetching blankets as they shuffle in and out of the hospital ward, speaking in hushed voices. They corral the nurses and discuss my aunt’s imminent departure in purely practical terms—heart rate and blood pressure? has she eaten or slept or toileted?—but no tears are shed. It has always been this way for them; any signs of weakness should be grasped at the root and removed. No use for softness or sensitivities – as I’m told ‘actions speak louder than words’. So it’s no accident that all my uncles and aunties work in trades that involve their hands. Aunty Sue heard the call of the open water and went overseas to work on yachts and catamarans. Gail went to university to become a physio.

After earning her degree, she’d worked in remote communities, eventually putting down roots in Roma, Outback Queensland. I imagine the red dust has settled into her bones, the stories of an ancient land, a biosynthesis which will carry her through these final breaths. Until the last leaf falls…

~

As an only child, I am a single leaf on the branch of a tree that has its roots implanted across two hemispheres. I’ve always felt out of sync with mum’s side of the family—I’m the outlier, the creative one; supposedly thin-skinned and too sensitive—and I wonder what drives any of these impulses within us. What drove my ancestors to migrate across oceans to Australia? And where do I fit in this story? I search upriver, following my maternal bloodline. In the scratch-on-a-map village of Orsago, my ancestors till the fields of Turin, in Northern Italy. Their migration to Australia comes in the late 1800s on the India – an ill-fated voyage launched by the Marquis de Reys, a French con man who has led several expeditions, luring hundreds of hopeful European migrants into his lucrative schemes to colonise supposedly uninhabited islands, promising wealth and prosperity in Utopie. Instead, they are abandoned on the remote shores of New Guinea, surrounded by inhospitable jungle and the rumoured threat of head-hunters [5]. If they make it that far. The families are subject to horrendous conditions aboard the ships – disease and malnutrition are rampant, particularly among the women, many of whom die in childbirth or from Pellagra, a niacin deficiency common in farming families that rely on subsistence diets [5]. On the ship, polenta remains a staple for the women, as the men and boys reap the protein-rich foods that allow them to keep their strength.

The journey my ancestors endure requires the strength of every man, woman and child. It is a miracle any of them survive, that I am here to tell their tale.

~

In her final hours, Aunty Gail shares two requests for her memorial service: we must dress in pink (for breast cancer awareness) and drink Prosecco (her beverage of choice). Rituals of death are for the living: we seek to memorialise and commemorate – verbs enacted for the departed by those that remain. But my aunt does not hold God, nor sentimentality, in her heart. Instead, she wishes for her death to advance the industry she’d contributed to in life: to donate her body to science. Specifically, to the medical school of her alma mater.

There’s just one problem: it’s three days before Christmas. The university has shut down its Body Donor Program for the year.

‘There must be something we can do,’ I say to Mum on the phone, exasperated. ‘People die every bloody day of the year, why should Christmas be an exception?’

But Mum is over a thousand kilometres away, and even the modern-day marvels of family video conferencing aren’t able to solve this dilemma. Aunty Sue, Gail’s appointed executor, establishes a family group chat. We employ shorthand: BDP for “Body Donation Program”. Every university within a 200km radius is contacted. ‘No one is accepting any donations,’ Sue tells us, distressed.

With university holiday shut-downs state-wide, and body donation laws differing interstate, we are left with two options and a narrowing window of time. We either find a suitable facility within the 150km ‘catchment area’ in the next 12 hours or forgo her final wishes and opt for a private cremation. It feels wrong not to honour Gail’s legacy: to donate her body in the knowledge it will be used to educate the next generation of surgeons, biologists, oncologists, physios and so on to advance scientific understanding [3]. Perhaps even spur a breakthrough in cancer treatment.

~

In 2020, a local author, Steve Capelin, approaches me to edit his historical novel, Paradiso. The novel delves into the Marquis de Reys’ expedition, of which Steve is a descendant. Struck by this serendipitous connection, I tell Steve of my own familial ties to the expedition – my great-great grandmother, Angelina Battestuzzi, was just thirteen when she’d arrived in Sydney Harbour aboard the India. I am beginning to find where I belong in this story.

‘What are the odds?’ Steve exclaims.

During the editing process, Steve and I exchange titbits of family history, he hands me a fragment of mudbrick and a CD-ROM of photos from another descendent who had visited Port Breton, the site where the India had landed in New Guinea back in 1880. I recall an identical mudbrick with a plaque on the mantel in Nonna’s house.

‘We have a brick just like that,’ I say, feeling the cell-tingling rush of awe. ‘But how did you get photos? These islands are so remote…’

‘The only way to get there is by private charter,’ Steve says. ‘The photos were taken by a friend of mine, Sue Mitchell, who’s also a descendant. She has her own yacht.’

A synaptic crackle. The photos had been taken by my Aunty Sue.

~

As live updates are fed down the line, I wonder what the donation of my aunt’s body might entail. Is there a screening process? A waitlist? Are there criteria a body must meet to be ‘accepted’ into the Program? I burrow down online rabbit holes, curious to know—what deems a body ineligible?

In fact, there are multiple reasons a body might be rejected [2] [3] [4], including amputation or autopsy, communicable disease, recent chemotherapy, or even dementia of an unknown cause. Evidently, where the death is reportable to the coroner, it’s an automatic red card. If the donor has been deceased for more than three days, it’s highly unlikely they’ll be accepted. Who knew the expired could have an expiry date?

There are even weight limitations. The body cannot be obese nor emaciated – that is, exceeding 100kg, or less than 50kg. I picture my frail aunt in the hospital bed. Would she be classified as emaciated? Even if we do find a BDP, there’s no guarantee they will take her. This is beginning to feel more like a lottery than a donation.

~

Imagine the planet is a dying body. Every living organism is a single cell within this body; there are eighty-six billion cells within the brain alone. But the body’s temperature is changing, fuelled by internal forces. Our body-planet is inching towards red alert, and some of its cells are feeling febrile. Given the choice, would you stay and accept this fate… or migrate? According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics [14], 30% of our country’s population are migrants, and half of us have at least one parent born overseas. The number of Australian immigrants is set to swell, with net migration reaching 650,000 people in 2023 [13]. The last spike in migration levels happened a century ago, post-WWI and following the Spanish Flu – our migrant ancestorspeople fleeing famine, drought, devastation and disease to find a better world. It seems like a case of history repeating itself, but with sea levels rising, increasingly unpredictable weather patterns and widespread food shortages, we are now facing unprecedented levels of mass displacement. How much of this “body” is going to be liveable in the years to come? When we’ve destroyed what’s left, where else do we go?

Escaping the dying earth is an idea we’ve leaned into hard over the past few decades and have come to embrace culturally. But is this literal moonshot more than just a popular science fiction trope? In the three decades since Kim Stanley Robinson’s Mars novels—a series that chronicles the settlement and terraforming of the red planet—the prospect of human settlement on Mars has diminished. Recent NASA missions have found chemicals—toxic to humans even in micro quantities—in the Martian soil. In his essay, ‘What Can’t Happen Won’t,’ (2015), Robinson concludes that human habitation on Mars is unlikely. ‘Even if you put machines to work, it would take thousands of years,’ he states. ‘So what’s the point? Why do it at all? Why not be content with what [we’ve] got?’

The (science) writing is on the wall: We cannot sustain the body-planet we have now if we keep doing what we’ve always done. Climate-induced mass migration is not just inevitable; it’s happening now.

~

The call comes at 6pm on Christmas Eve. We’re on Aunty Sue’s yacht S Y Lola moored at Hope Island, but no one is feeling festive – or hopeful. Exhausted, we roll out a picnic rug on the aft deck, peel some cold prawns and down our glasses of Prosecco. Salute!

When Sue’s phone rings, I feel a giddy surge, and it’s not just the bubbles. ‘It’s a call-back from one of the universities,’ she says.

The BDP representative goes above and beyond: the donation of my aunt’s body is accepted. They handle every aspect, even transporting her body from the hospital. The facility is in Brisbane city, so the transfer is straightforward and, thankfully, free-of-charge.

I struggle to sleep that night, but unlike my child-self trying to stay awake long enough to glimpse reindeer or hear sleigh bells, I am in a whirling tundra of body donor questions. What happens now? Where is my aunt’s body? The in-between?

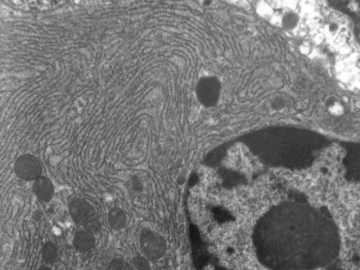

According to one BDP, donated bodies are either frozen or embalmed for two months prior to dissection. Then, in order to display anatomical features such as muscles and ligaments, sections may be plastinated. [4] Plastination is the eighties brainchild of Polish anatomist, Dr. Gunter von Hagens [8]. It’s a process that involves replacing body fluid and wet tissue with cured polymer, rendering the specimen dry and safe to handle [4]. In addition, the organs may be removed for research into certain diseases, and to better understand anatomical composition. [2].

I am simultaneously awed and repulsed, imagining squelchy innards and bodily fluids replaced with plastic. A kind-of cadaver Barbie.

In the university’s Skeletisation Program, the bones of the body are removed and catalogued, providing a ‘library’ of skeletal material for teaching and research purposes. Skeletisation is a technique whereby all soft tissue is extracted from the bones, followed by a process of chemical and natural cleansing—for example, the application of flesh-eating dermestid beetles—prior to labelling and addition to The Collection. [4]

I am left with my vivid imagination to conjure what will become of Aunty Gail after her two months, frozen or embalmed, are up.

Either way, The Collection sounds formidable.

~

We gather for the memorial in early March 2023. The university provides donor families an opportunity to pay respects to loved ones [3]. Bowed heads, we mourn in pink and clink our glasses as a sign of respect. Among the clusters of black, our brightly clad clan stands out. It’s strange to mourn in this communal way, where there are other families and other bodies to be grieved for. Speeches are given, but it’s hardly a recruitment drive: BDPs are, generally speaking, booming. One university claims more than 13,000 registrations, with 250 of those registrants becoming potential donors (dying) each year. BDPs accept fewer than fifty percent of these donations [4]. The fact that one of them accepted my aunt’s body—a 72-hour-old, slightly emaciated, cancer-riddled offering—is nothing short of a miracle.

~

What do we learn about our own lives in watching death, and in caring for the dying? Well, for one, I view my own body differently now: I see it as an object of purpose and function. A conscious vessel of flesh and bone with an expiry date. Life is no stroll in the intergalactic park – and neither is death, it seems. Until now, I’d never put much thought my own mortality, let alone whether I’d want my body to be buried or cremated – or donated.

According to a recent article in The Conversation, we may not have a choice.

The Australian housing crisis in not just an issue for the warm bodies among us: cemeteries in densely populated cities such as Sydney will run out of space by 2032, and measures are being put in place for sustainable alternatives to traditional funeral practices such as green burials, water cremation, and, of course, body donation [11]. So, when my time comes, I’ll be taking a leaf out of Aunty Gail’s book and donating my body to science. (I figure my pre-programmed cell death means I won’t even notice the peckish beetles.)

I’d always speculated at the ways I can make a difference in life—through, say, the words I write—and now I think of what my body could do and be in death.

References

[1] Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, et al. (2002) ‘Programmed Cell Death (Apoptosis)’ in Molecular Biology of the Cell. 4th edition. New York: Garland Science. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK26873/ (accessed 1 March 2023)

[2] ‘Become a donor’ (2023) Griffith University Body Donor Program. Available from:

https://www.griffith.edu.au/griffith-health/school-anatomy/become-a-donor (accessed 28 February 2023)

[3] ‘Body Bequest Program’ (2023) Queensland University of Technology, available from:

https://www.qut.edu.au/engage/giving/ways-to-give/body-bequest-program (accessed 28 February 2023)

[4] ‘Body Donor Program: Frequently Asked Questions’ (University of Queensland)

https://biomedical-sciences.uq.edu.au/engagement/body-donor-program/body-donor-program-frequently-asked-questions (accessed 28 February 2023).

[5] Capelin, S. (2021) Paradiso: A Novel. AndAlso Books, Brisbane, Australia

Available from: https://www.andalsobooks.com/paradiso-a-novel

[6] Ferrazzi, K. (2010) ‘Three Degrees of Influence: How far can you reach people?’ excerpt published on Cornell University blog: https://blogs.cornell.edu/info2040/2015/10/19/three-degrees-of-influence-how-far-can-you-reach-people/ (accessed 29 February 2023)

[7] Gilbert SF. (2000) ‘Morphogenesis and Cell Adhesion’ in Developmental Biology (6th edition). Sunderland, MA. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK10021/ (accessed 3 March 2023)

[8] ‘Gunter von Hagens: Inventor of Plastination, Creator of Bodyworlds’ (2023). Available from: https://bodyworlds.com/plastination/gunther-von-hagens/ (accessed 10 March 2023)

[9] Keely, P.J. (2013) ‘Cell Migration within Three-Dimensional Matrices’ in Lennarz, W. & Lane, D. (Eds). Encyclopedia of Biological Chemistry (Second Edition), Academic Press.

Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780123786302004953

[10] Villazon, L. (undated) ‘What happens to cells in our bodies when they die?’ in BBC Science Focus: https://www.sciencefocus.com/the-human-body/what-happens-to-cells-in-our-bodies-when-they-die/ (accessed 29 February 2023).

[11] Falconer, K & Gould, H (2023) ‘Our cemeteries face a housing crisis too. Four changes can make burial sustainable’ in The Conversation: https://theconversation.com/our-cemeteries-face-a-housing-crisis-too-4-changes-can-make-burial-sustainable-205987 published 29 May 2023 (accessed 14 July 2023)

[12] Rothman, J. (2022) ‘Can science fiction wake us up to our climate reality? Kim Stanley Robinson’s novels envision the dire problems of the future—but also their solutions’ in The New Yorker, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2022/01/31/can-science-fiction-wake-us-up-to-our-climate-reality-kim-stanley-robinson published 24 January 2022 (accessed 14 July 2023)

[13] McDonald, P. (2023) ‘What’s behind the recent surge in Australia’s net migration – and will it last?’ in The Conversation, https://theconversation.com/whats-behind-the-recent-surge-in-australias-net-migration-and-will-it-last-203155 published 5 April 2023 (accessed 19 July 2023)

[14] Australian Bureau of Statistics. ‘2021 Census: Nearly half of Australians have a parent born overseas’ in ABS, 27 June 2022, https://www.abs.gov.au/media-centre/media-releases/2021-census-nearly-half-australians-have-parent-born-overseas (accessed 19 July 2023)