What Comes First is a Question

Jessica White

In the opening of Lab Girl, her memoir about becoming a scientist, Hope Jahren exhorts her reader to look outside their window. Amidst buildings and sidewalks, they might catch a glimpse of something green: a tree. This is ‘one of the few things left in the world that humans cannot make,’ she says. She directs her reader to look closer and to focus on one leaf. Jahren, a geobiologist who analyses plant fossils, asks questions of leaves such as ‘How hydrated is the leaf? Limp? Wrinkled? Flush? What is the angle between the leaf and the stem?’ She turns back to the reader and tells them, ‘Now you ask a question about your leaf.’

‘Guess what?’ she continues. ‘You are now a scientist. People will tell you that you that you have to know math to be a scientist, or physics, or chemistry. They’re wrong. That’s like saying you have to know how to knit to be a housewife, or that you have to know Latin to study the Bible. Sure, it helps, but there will be time for that. What comes first is a question, and you’re already there.’

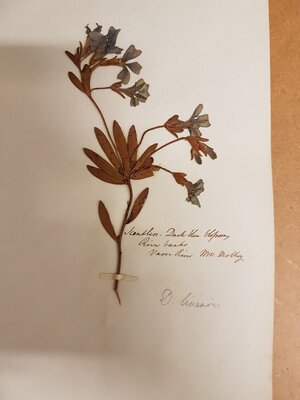

For more than twenty years I have been thinking about the question of Georgiana Molloy, one of the first colonisers at what is now known as Augusta in south-west Western Australia. From 1836 until her death in 1843, Georgiana, whenever she could scrape time from caring for her children and darning socks, strode into the bush. Her nimble fingers plucked the red blooms of Kennedia prostrata and fixed them into a book of blank pages called a hortus siccus (Latin for ‘dried garden’). She ferreted tiny seeds from pods, or siliques as she called them, slipping them into cloth bags that she sewed herself. She carefully numbered each specimen in the book and its corresponding seeds, then shipped them, whenever a vessel arrived in the bay, to a horticulturalist in London named Captain James Mangles.

Each plant was a question: what are you? But because Georgiana was a woman and was not permitted to be part of the Royal Society for scientists, lacked formal training in botany, and lived fifteen thousand kilometres from the imperial centre of science in Britain, she had to wait — sometimes for a year or two — for Mangles to answer with the Latin names of the plants she collected. While she waited, she continued to collect, focussing fiercely on plants she had never seen before, asking herself questions about their morphology, flowering times and the soils in which they grew best, and learning at least one Noongar word for a plant (danja, the Western woody pear, or Xylomelum occidentale, although at the time she thought this was a hakea). In answering these questions about what plants were and how they grew, her knowledge of the flora of south-west Western Australia expanded exponentially, to the point where a visiting minister, Reverend John Wollaston, called her a ‘perfect botanical dictionary.’

Georgiana’s life raises a number of questions for me about colonisation, aesthetics, feminism, writing, climate change and biodiversity. And one to which I repeatedly return: why has her work as a scientist been so consistently overlooked? To answer this, I need to turn back to the development of her scientific life.

*

Botany was all the rage in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, prompted by the Enlightenment’s focus on science and discoveries from newly colonised lands. In 1735, in a sustained attempt to order the names and plants that voyaging naturalists brought back to Europe, Carl Linnaeus published his Systema Naturae. In this, he elaborated on the system now known as binomial nomenclature, or the means by which living things are named first according to their genus, and then the species within that genus. Ordering and classifying plants became much easier for European scientists through this system, but women often lacked access to it because it was in Latin, and few women were educated in Latin.

From the 1760s onwards, however, books about botany were increasingly written with women in mind. Botany, like other decorative arts such as painting and flower arranging, began to be seen as a worthwhile pursuit for women because it combined leisure and learning. As Ann Shteir writes in Cultivating Women, Cultivating Science (1996), botany encouraged women to head outside to collect plants and create herbaria. They learned botanical Latin and botanical illustration, and studied plant physiology with microscopes. In this way, although they could not be members of the Royal Society or Linnean Society, attend meetings at these societies, or publish (with rare exceptions) in their journals, they could still participate informally in science.

Born in 1805 to a wealthy family, Georgiana was familiar with plants. Her father built a walled garden and a tree-lined drive on their estate near Carlisle, and when she stayed with friends in Scotland as a young woman, she gardened and collected flowers as souvenirs. In 1829 she married Captain John Molloy, a soldier who’d fought in the Napoleonic Wars. Finding promotion elusive, and wearying of life in the army, Captain Molloy planned to emigrate to the new colony at Swan River (now Perth) in Western Australia. In marrying him, Georgiana knew she would likely never see her family and friends again. Among the items she packed for her new life was a hortus siccus, indicating that she had been educated in the ‘polite’ art of botany and that she knew how to collect and dry plants.

The Molloys arrived at Swan River in 1830 and found the settlement process in chaos. Seeing that there was little government-allocated land available, they sailed three hundred kilometres south to a new outpost, Augusta. Georgiana was by this stage heavily pregnant, and two weeks after their arrival at Augusta, she gave birth in a canvas tent by the shore in pouring rain. The baby was not well and, over the course of ten days, her health declined until she died. To ‘dispel the sad blank her death occasioned,’ Georgiana wrote to her friend Frances Birkett in 1831, she went out and planted bulbs. When the time came for the funeral, Georgiana picked a blue native flower and placed it on her daughter’s grave. Despite her turmoil she responded, poignantly, to her environment.

A year later, James Mangles, cousin to Ellen Stirling, the wife of the colony’s governor, made a visit to Swan River. Mangles had entered the navy at age fourteen and spent fifteen years at sea, reaching the position of officer before he left in 1815. The next year, he travelled with his friend Captain Charles Leonard Irby, a messmate from his earliest years in the navy, to Egypt, Syria and Asia Minor. In July 1819 in Genoa, on his return from this journey, he met John Claudius Loudon, a Scottish botanist, landscape and garden designer, and a prolific author. Loudon may have ignited Mangles’ interest in flowers and gardening, for he went on to develop connections with the Loddiges nurserymen of Hackney in London (notable traders in exotic flora), and with Joseph Paxton, gardener at Chatsworth and designer of the Crystal Palace for the 1851 Great Exhibition. He also became a member of the Royal Society and the Royal Geographical Society.

Flora may have been on his mind during his sojourn at Swan River due to the excitement about Australian plants in Britain. A few years later, he wrote to emigrant George Fletcher Moore and requested him to collect Australian specimens and seeds. A fellow colonist, James Drummond, independently approached Mangles and offered to collect for him commercially, an offer which Mangles accepted. Through Ellen Stirling, Mangles also wrote to Georgiana. In 1836 he sent her a box of English seeds and a letter requesting ‘a return of the Native Seeds of Augusta.’ It was not seemly to pay a lady as he paid Drummond, so the English seeds were the first in a long line of gifts that he sent her over the years.

In her first, brief reply to Mangles, dated 31st March 1837, Georgiana complained of a lack of time to collect, for ‘all my former pursuits have necessarily been thrown aside (by the peremptory demands of my personal attention to my children and domestic drudgery).’ She had, by this stage, given birth to two daughters and a son. In November of that year, her nineteen-month-old son wandered off after breakfast, fell into a well and drowned. This terrible accident precipitated what Georgiana described as a ‘dangerous illness,’ likely a nervous breakdown. To take her mind from her grief, Georgiana applied herself to Mangles’ project with vigour. In a letter dated 1st November 1838, she wrote to him, ‘Since my dear Boy’s death I have, up to the present time, daily employed myself in your service.’

Georgiana’s collecting for Mangles ripened into an obsession. In a letter begun in June 1840, she wrote, ‘scarcely a day passes I am not thinking what I can do or how in any way I could promote your cause.’ Earlier that year, she gushed, ‘I never met with anyone who so perfectly called forth and could sympathise with me in my prevailing passion for Flowers.’ Her words show how intellectually isolated she was in the settlement at Augusta, and how she felt she had found her calling. On 22nd June 1840 she wrote, ‘when I sally forth either on foot or Horseback, I feel quite elastic in mind and Step; I feel I am quite at my own work, the real cause that enticed me out to Swan River.’ Collecting had become a vocation for her, to the point where, in a letter of 25th January 1838, she confidently stated:

I have no hesitation in declaring that were I to accompany the box of Seeds to England, knowing as I do, their situation, time of flowering, soil and degree of moisture required with the fresh powers of fructification they each possess — I should have a very extensive conservatory or conservatories of none but plants from Augusta.

This shows that Georgiana was working as a scientist. She asked of her plants where they grew best, when they flowered and how much water they needed to grow. Yet, immediately after this statement, she added, ‘I do not say this vauntingly, but to inspire you with that ardour and interest with which the collection leaves me.’ To remain appealing to Mangles, she needed to maintain an identity that was feminine and modest, rather than assertive.

A century later, the dichotomy between science and femininity is still entrenched. Jahren, when she was five, decided that her real self looked exactly like her scientist father, ‘even though on the outside I was disguised as a girl.’ She spent her time ‘deftly grooming myself and gossiping with my girlfriends about who liked whom and what if they didn’t.’ Then, in the evenings, she accompanied her father to his lab, where she ‘transformed from a girl into a scientist.’ Although Jahren, through her engaging account of building research labs three times from scratch, rejects the idea that women can’t do science or be scientists, it is clear that she must work harder than her male counterparts to prove her worth. Georgiana, meanwhile, received no recognition for her efforts, other than gifts of silk and books from Mangles, even as he gained prestige for sending her collections to prominent men in botany such as John Lindley, the first Professor of Botany at University College London. And while more than one hundred specimens were named for Georgiana’s contemporary, James Drummond, only one plant — Boronia molloyae — was named for Georgiana posthumously in the 1970s. The Noongar guides and collectors whom Georgiana and Drummond relied upon are yet to receive formal recognition.

*

I often imagine Georgiana walking through the shade cast by tall jarrah and marri trees, twigs and grass caught in her hems. Her daughters run ahead, their sharp, high voices calling out as they find a flower. Georgiana moves towards them, murmuring the Latin names that arrived with Mangles’ last letter, wrapping them around her tongue like honey. When she reaches the bright yellow flower she slips a finger beneath its tapered petal. ‘Caladenia flava,’ she says to her daughters. ‘A spider orchid. It looks like a cowslip.’

Georgiana worked relentlessly to gather knowledge about the plants in her new environment, waiting for their Latin names from Mangles, and carefully arranging and pressing them into her horti sicci. In 1839, John Lindley, the Professor of Botany, published an Appendix to the first twenty-three volumes of Edwards's botanical register … together with a sketch of the vegetation of the Swan River colony. Mangles sent Georgiana a copy of this volume, which describes a number of the plants she had collected, as well as others from the south-west. Although Lindley mentioned her ‘zeal in the pursuit of Botany’ he did not list her in his acknowledgements. Georgiana, unfailingly polite, thanked Mangles for the gift and described it as a ‘key’ to the plants she collected.

Georgiana never once asked for recognition, but as I watch her crouching beside the bright orchid and her daughters, I find myself compelled to voice her unspoken question: When will I be recognised for my science?